For as long as I can remember, I’ve had a great love for nature, especially for birds.

Case in point, it has been over 40 years now since my dad gave me my first exposure to the world of bird watching as we both casually walked the main dike at Farmington Bay, binoculars in hand and eyes to the sky.

Wow, I can’t believe it’s been that long ago but I still remember it as if it was yesterday.

A lot has changed for me since that unforgettable Saturday morning as a wide-eyed youngster getting his first real taste of birding, but rest assured, one thing, my passion for wild birds, has only continued to grow since then.

And nowadays that passion isn’t just for bird watching itself but a strong desire to encourage other people through this website to get interested in wild birds as well.

Lately, because of my near obsession-like craving for the challenge of nature photography, I have been drawn to the smallest raptor of North America, the American kestrel.

Kestrels are truly beautiful birds, but one that doesn’t often lend itself to easy photography efforts like many other birds do.

Ask any bird photographer and they will tell you the same thing, American kestrels can be quite difficult and very frustrating to photograph.

So any and every chance I get to photograph an American kestrel I take full advantage of to try and get even an acceptable representation of this magnificent falcon regardless of the situation it was found in.

A couple days ago on Antelope Island, I came across an American kestrel sitting on a less than gratifying perch, a garbage dumpster, but I decided to stop and take a photograph anyway because, after all, it was a kestrel.

As common for kestrels, the small falcon sat still for only a few seconds before flying away, but I was able to get a couple very interesting images before the bird flew off to a more distant perch.

I wasn’t aware until I viewed the images a bit later but that male American kestrel had a large green band on one of its legs and a small silver band on the other.

Immediately, I tracked down Steven Bates, the biologist for Antelope Island, where I learned the kestrel was banded by HawkWatch International, the non-profit raptor organization that currently monitors the American kestrels on the island.

I’m pretty familiar with and quite interested in bird banding but I had completely forgotten American kestrels are actually being banded on Antelope Island by HawkWatch International.

Bird banding is a long-time practice performed by researchers and biologists to help track birds’ movements and migrations as well as learn about the life spans and breeding efforts of specific birds.

(As a side note, for those of you not familiar with my experience last summer of helping Amiee Van Tatenhove, a USU Ph.D. student working to capture and band American white pelicans for a research project, I offer you to, later on, read my blog post about the experience, it was one of the most amazing things I have ever experienced, to say the least.)

In a nutshell, bird banding consists of catching a bird and placing a small, aluminum band on one of the birds’ legs.

Each band has a unique number the banded bird will forever be associated with.

Data such as banding location, date, sex, age, for example, are taken and recorded in a federal database at the USGS Bird Banding Laboratory, and when the bird band is observed again and reported, the new date and location can be used to help track the birds’ movements and lifespan of the bird.

Over time and with years and years of data, migration routes, lifespans, and a host of other important information can be collected and learned about a particular species of bird through bird banding.

Alright, it’s a little bit more complicated than that actually but simply put, a bird is caught and tagged so it can be observed later on, hence giving researchers valuable data on the birds’ whereabouts and longevity.

But the key to all of this is the bird not only has to be initially caught and leg-banded, but the bird has to be observed later on and the small numbers read and recorded, something nearly impossible to do unless the bird is harvested, in the case of waterfowl during the hunt, or the bird is recaptured by another researcher, something not always commonly done, however.

Over time, researchers have come up with ways for more people to observe band numbers on birds where they don’t have to be recaptured or harvested and citizens like you and me can actually help observe and report such band sightings even from our everyday bird watching trips.

Larger colored bands are placed on the bird’s leg where the numbers can be observed from a distance with a spotting scope, binoculars, or in my case, photographs.

It still requires someone spotting the bird, correctly reading the band numbers, and reporting them but it means less stress on the bird by not having to be recaptured for important data about the bird to be collected.

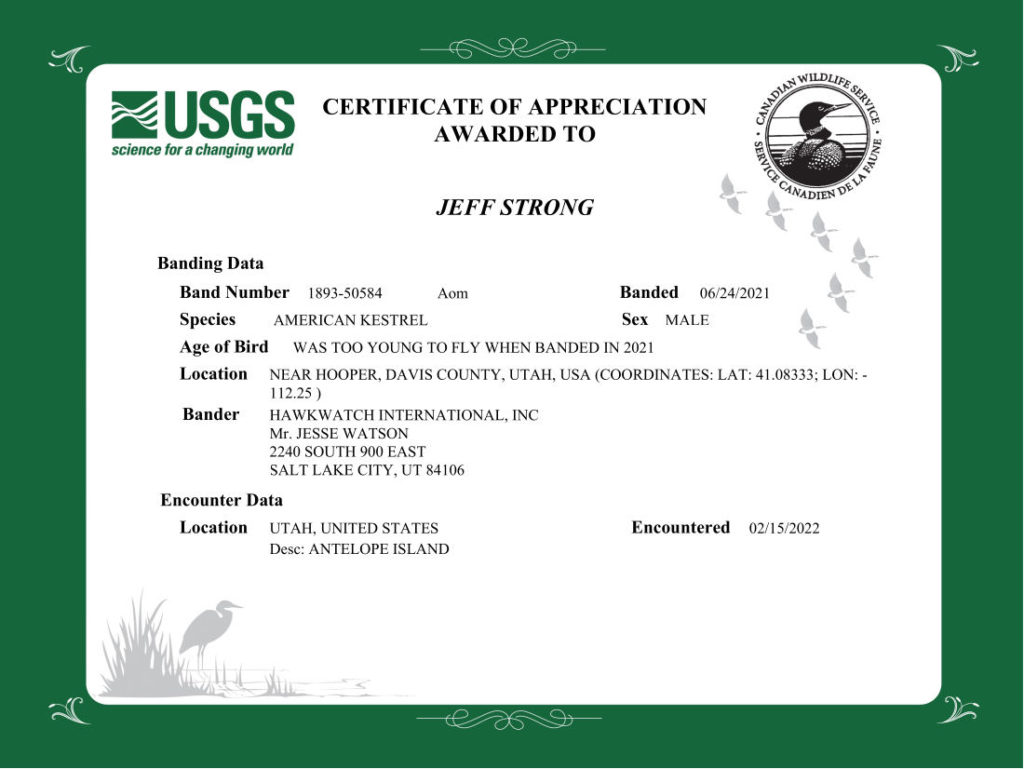

After getting in touch with Jesse Watson, Research Biologist and Banding Coordinator with HawkWatch International, I was able to track down some information about this particular American kestrel and receive a digital Certificate Of Appreciation from the North American Bird Banding Program, which is under the general direction of the U.S. Geological Survey and the Canadian Wildlife Service.

From the banding data, I was able to learn this male American kestrel was hatched last year on Antelope Island and had 3 other kestrel siblings from that same nest that also fledged.

HawkWatch International volunteers and staff monitor all 20 kestrel boxes, artificial nests put up for more breeding locations, on Antelope Island during each breeding season to continue to compile data on the American kestrel in hopes of learning more about breeding success as well as banding as many kestrels as possible to help understand more about their movements and migration routes.

Monitoring American kestrels goes beyond just Antelope Island, however, as HawkWatch International studies actually span an 80 mile north/south corridor from Willard Bay to Orem, Utah.

Last year, out of the 20 kestrel boxes on Antelope Island, 11 boxes were active with three of them eventually producing a total of 9 kestrels for the season.

American kestrels are cavity-nesting birds but don’t excavate their own nesting cavities, meaning they typically use, for example, holes already in trees as their nesting locations that are oftentimes created by woodpeckers and flickers.

And when natural cavities aren’t available, artificial nesting boxes, casually termed “kestrel boxes”, are used in their place with a lot of success and can even be placed in areas without trees, thus adding more locations for kestrels to breed when natural places are limited or non-existent.

Kestrel boxes also make it much easier for researchers to monitor nesting sites and band chicks and adult American kestrels caught in the box, helping to further the gathering of much-needed data on this declining raptor species.

I’m actually in the process of adding a kestrel box to my property this spring as American kestrels are quite common in my yard because of the large grove of trees and numerous house sparrows it attracts.

A couple years ago, I was actually on Antelope Island when interns from HawkWatch International were monitoring active kestrel boxes and ended up capturing and banding an adult male American kestrel from one of the artificial nests.

A large colored auxiliary leg band was placed on one leg and the standard small aluminum band was placed on the other leg of the kestrel.

Measurements and photographs were also taken of the bird, then the male American kestrel was released.

According to the HawkWatch International website, some of the kestrel project highlights include 3,094 American kestrels that have been banded so far by the organization, including 1,817 color-banded individuals like the one I photographed the other day.

HawkWatch International urges birders, photographers, and anyone else that observes a banded American kestrel to report it to their website, noting the sex of the kestrel, color of the leg band, which leg it was on, and the alphanumeric code, the date, and location the kestrel was observed.

Keep in mind not all American kestrels have colored leg bands so if you come across one that just has the standard small silver aluminum band, it was most likely banded by HawkWatch International and they still want to know of the observation even if no band numbers were obtained.

I for one always look at the legs of American kestrels whenever I see one in hopes of finding a banded bird.

So far, I have only found the banded kestrel at Antelope Island, but with luck, I may come across another one in my travels as a bird watcher and photographer.

Keep your eyes out for not only leg-banded American kestrels but any other potentially banded bird you are watching.

So far, in addition to the banded American kestrel, I have seen leg bands on snow geese, tundra swans, Canada geese, northern pintails, mallards, a yellow-headed blackbird, and a loggerhead shrike so you just never know what you will find when you go bird watching.

American Kestrel T-shirt, available in a variety of colors and styles. Visit Bird Shirts and More for more information or to make a purchase, and use coupon code save20 for 20% off for a limited time.

If you are a bird watcher like I am, I offer you to head on over to our subscribe page and sign up for email notifications for future blog posts.

Bird watching is our main passion for this website but we also blog about many other interesting things in nature we find along our way.

We also have a small but growing YouTube channel where we post occasional video updates about the Bear River Migratory Bird Refuge as well as short nature clips when we are able to film them.