It’s not as uncommon as we might think, at least from my own birdwatching experience I would say.

What I am referring to is finding a wild bird with some kind of numbered band attached to one of its legs.

I was reminded of this a couple days ago when I was doing a little birdwatching at Farmington Bay and my camera and I crossed paths with a female American kestrel with a yellow plastic leg band on its left leg.

The kestrel was very patient as I watched and photographed it for a few minutes while it worked on eating some kind of rodent it had just caught.

And it wasn’t until just before it flew off after a magpie started to pester it that I noticed the yellow plastic leg band.

Fortunately, I was able to take a few sharp images of the band which allowed me to accurately read and report the band to the appropriate government agency.

Each year, many species of wild birds all across North America, including American kestrels right here in Utah, are caught by biologists, fitted with leg bands, and released back into the wild.

It’s a very common practice with waterfowl, namely ducks, geese, and swans, but even non-game bird species such as American kestrels are continually caught and tagged in such a manner by biologists.

So why is this happening and what should we do when we see one of those brightly colored leg bands?

First off, tagging wild birds with colored leg bands is one way biologists can help track their local and long-distance movements, including migration routes.

In turn, finding out where birds live throughout the year helps determine which areas are needing protection from development and other uses that degrade and reduce wildlife habitat for birds.

Once a wild bird is trapped, tagged, and released the information on where and when the bird was originally caught will be compared to any additional sightings if the bird is observed again and reported to the Bird Banding Laboratory.

Observing birds over and over in such a manner can greatly help answer the sometimes unknown questions about where specific birds migrate to each winter.

The only caveat is, however, the banded bird has to be seen, identified by the numbers on the colored leg band, and reported to the Bird Banding Laboratory, which is part of the Patuxent Wildlife Research Center in Maryland.

This is where you and I as birdwatchers can get involved in the process.

Anyone that finds and identifies a wild bird by a colored leg band, similar to what I have recently found on this American kestrel, can and is highly encouraged to submit their findings to reportband.gov, the official reporting website for the Bird Banding Laboratory at the Patuxent Wildlife Research Center.

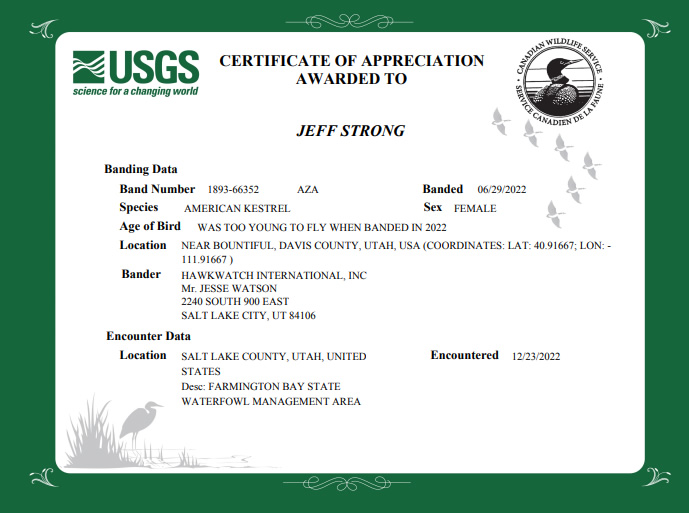

Once your observation is submitted and retrieved through their website, you will be emailed a certificate of appreciation which gives some details about when and where the bird was originally caught and banded.

By reporting any and all leg-banded birds we might encounter on our birdwatching trips to the Bird Banding Laboratory we all can help unlock the mysteries of bird migration and movements.

In the specific case of American kestrels out here in the western United States, Hawkwatch International has an ongoing kestrel banding program to help study kestrel migrations and movements in this part of the country.

In Addition to reporting it to the Bird Banding Laboratory, leg-banded American kestrel sightings can also be submitted to Hawkwatch International as well since many of the banded kestrels out here in the west are part of their ongoing research study.

So if you are out and about doing a little birdwatching or photography, keep a sharp eye out for leg-banded wild birds.

If you do find a wild bird of any species with a colored leg band, try and accurately record the number, the color of the band, and which leg it was on as well as the species of the bird if possible and report it to the Bird Banding Laboratory to help with the ongoing research pertaining to bird migration.

Taking a few pictures of the bird and the leg band if you happen to have a camera with you is what I find works best to help read the numbers as birds don’t oftentimes sit still long enough to accurately read the band numbers with just the naked eye.

If you’re into nature and especially birds like I am, I offer you to head on over to our subscribe page and sign up for email notifications for future blog posts like this one.

We also have been putting some time into growing our small YouTube channel where we post updates about the Bear River Migratory Bird Refuge and other places we frequent for this blog as well as a few occasional short nature clips when we can find and record them.