I don’t know how else to categorize it but it’s sure been an atypical season for my birdwatching excursions this winter on the Bear River Migratory Bird Refuge, to say the least.

And from what I can tell, the birdwatching oddities just keep rolling in as if they were now considered to be the new normal.

A partial list of peculiarities I’ve both recently seen and photographed includes a flock of American avocets cruising by the day after Christmas, numerous white-faced ibis feeding in iced-over wetlands all winter long, several greater yellow legs a thousand miles or more from where they should be this time of year, and now this, photographing a flock of pelicans standing in the snow during late-January.

Did I just say photographing pelicans in the snow in January?

Those are three words, pelicans, January, and snow, I thought I’d never put together in the same sentence, ever, but I guess never say never when birding, right?

Today’s most unusual sighting of a dozen American white pelicans casually sitting on a snow-covered bank just a hop, skip, and a jump from other fish-eating birds, namely great blue herons, intently standing over small, random ice holes scattered throughout a tightly frozen wetland in hopes of a much-needed meal to swim by definitely takes the top spot of head-scratching observations in my birdwatching book for sure.

American white pelicans are a very common bird here in Utah during the summer when Gunnison Island attracts one of the largest pelican breeding colonies in the country to its remote location in the far reaches of the Great Salt Lake’s northern arm.

In fact, in past years as many as 21,000 breeding American white pelicans have been observed on Gunnison Island so, suffice it to say, pelicans are a very common bird along the Great Salt Lake wetlands of northern Utah during the warmer months of the year.

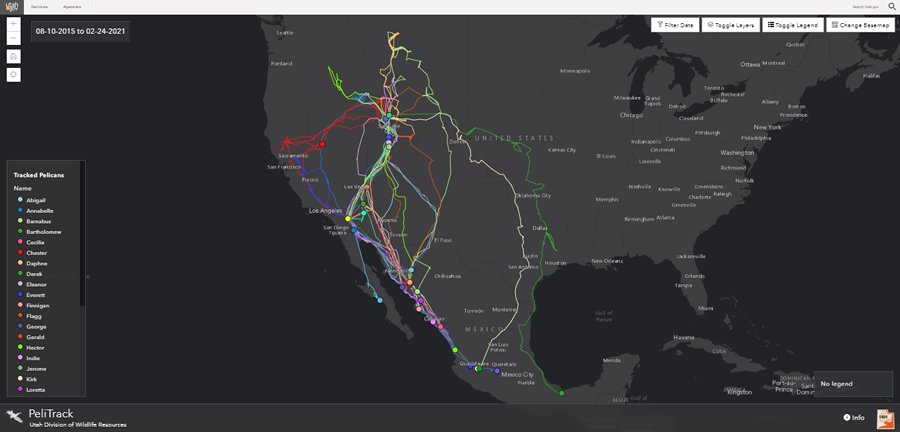

But being a fish-eating bird, when the water freezes pelicans lose their food source so they migrate south to warmer climates, sometimes as far south as central Mexico, to find fish and a more temperate environment for the winter season.

It’s not necessarily the cold or even the snow that drives them south but the upcoming seasonal lack of access to food, mainly carp and other freshwater fish, due to frozen freshwater lakes and rivers which is the main factor for their annual departure.

Pelicans know this and typically during fall, sometimes even as late as early November in mild years, they have already left northern Utah and migrated south for the winter, flying as far south as central and southern Mexico with some stopping short in parts of California or even the southwest corner of Arizona.

Interestingly enough, pelicans from other parts of the continent migrate from as far north as central Canada after the breeding season to not only Mexico but also to the Gulf coastal states, locations ranging from Texas to the southern tip of Florida.

As you can see these are all warmer climates and regions where fish and open water aren’t in short supply so it’s very peculiar to find a dozen or so pelicans sitting on a snow-covered bank adjacent to an ice-covered Bear River Migratory Bird Refuge auto tour route in late January when most of the refuge and the nearby Bear River that fills the sanctuary is, well, to put it mildly, frozen solid.

It’s not the first time I have seen pelicans in Utah during winter, however, last February I came across quite a few pelicans at Farmington Bay feeding in a pocket of open water but this is without question the earliest I personally have seen pelicans here in northern Utah.

And to make this strange occurrence even more odd for me, online conversations with other birdwatchers have netted the fact a couple other birders have seen small flocks of American white pelicans stay all winter long the past several years in certain locations in northern Utah, including Farmington Bay and Utah Lake.

I would never doubt such claims by any means as the only thing we birders can truly count on is sometimes finding such peculiarities when we least expect it but I do wonder how and where those wintering pelicans found enough fish during the winter months to sustain themselves during the frigid, sometimes arctic temps we oftentimes get here in Utah during late December through January.

As for these “oddities” in nature, it’s not that they don’t happen, they most certainly do and these unusual occurrences might even be trending towards the more common side of things with each turn of the calendar, possibly due to an ever-changing world and environment, we just don’t know.

In fact, another very unusual occurrence just a few summers ago involved a different species of pelican, a brown pelican that’s rarely seen in Utah, which visited the Bear River Migratory Bird Refuge for a few weeks or more and intrigued birdwatchers and photographers alike, myself included, as it flew up and down the Bear River diving for fish along its way.

But putting the reasons behind crossing paths with a bird when and where we would least expect to see it aside for a moment, such discoveries are, in fact, some of the greatest thrills in all of birdwatching and one of the driving forces that keep me firmly interested in our feathered friends ever since I was a kid walking the dike at Farmington Bay with my dad on what was my first ever birdwatching trip over 40 years ago.

(Pelican Feeding Frenzy. For short nature clips like this one and interesting stories about the natural world around us, check out our Bear River Blogger channel on YouTube for videos and updates from our travels while out in nature, both on and off of the famed Bear River Migratory Bird Refuge.)

If you’re like me, an avid nature nerd and birdwatcher, through and through, I offer you to head on over to our subscribe page and sign up for email notifications for future blog posts like this one where we share our love of birds and nature through both photography and the written word.

And for those birdwatchers who are highly interested in the comings and goings on the Bear River Migratory Bird Refuge auto tour route, we also offer you to check out and follow the Bear River Blogger Podcast on our YouTube channel where we routinely drive the 12-mile loop and share with others what we are seeing and when they are being seen.