For as long as I’ve been interested in birds, a period spanning well over 4 decades, the American white pelican has grabbed hold of my heart and hasn’t let go ever since.

But, in all fairness, what bird watcher isn’t mesmerized, at least a little bit, mind you, by a flock of pelicans grabbing a thermal and effortlessly soaring high above on a hot summer’s day.

It’s quite ironic if you think about it, pelicans are so beautiful, so graceful on the wing, but yet, so awkward, maybe even somewhat clumsy, on land.

Nevertheless, despite these polar opposites, pelicans are quite an interesting bird to watch, photograph, and study.

This past summer and thanks to Aimee Van Tatenhove, a promising Ph.D. candidate at Utah State University studying pelicans for her degree, my fondness for these masters of migration has reached even new heights.

It was a couple fun-filled days, oftentimes in mud up to my thighs, of helping Aimee with her pelican research that gave me a whole new perspective on pelicans, as well as a great appreciation for what goes on behind the scenes just to study wildlife.

And without giving too much away too early in this blog post, call me crazy but boot-grabbing marsh mud and American white pelicans are two key ingredients for a great afternoon.

You’re just going to have to trust me on that for now so keep reading, I’ll explain more as this post goes on.

This past summer, I met Aimee on one of my random trips around the Bear River Migratory Bird Refuge auto tour route where she and a couple of volunteers were casually watching the vast open waters of unit 2.

With a shade canopy and spotting scope prominently set up in the small parking lot, I just had to pull over and see what was going on.

I didn’t quite understand at first what Aimee was up to, but it was interesting enough I had to stick around and learn more.

And I am quite glad I did because Aimee gave me the experience of a lifetime the following week, something I never dreamed of in a million years I would get to do but did a few days later after that chance meeting on the refuge auto loop.

But before I get into that, let me talk a little bit about Aimee Van Tatenhove and her Ph.D. research with the American white pelican.

From what Aimee’s parents told me, she is a, well, science nerd, (her parent’s words, not mine) for lack of a better term I guess.

She has been into science and nature for as long as her parents can remember, and it shows through how much enthusiasm and knowledge she has for her research project.

Aimee obtained her bachelor’s degree at the famed ornithology school Cornell University in the field of natural resources, and when this opportunity came up for her to jump to the Ph.D. level at USU, she took it.

From what she has told me, her interest in studying and working with birds after she gets her Ph.D. is with seabirds.

From my perspective, despite not being an actual seabird, studying pelicans seems to be a pretty close similitude so I can only think it’s a pretty good fit, nevertheless, for her long-term aspirations in the field of wildlife management working with seabirds someday.

Having spent some time in graduate school myself, I can attest to just how hard it is to get into an upper-level field of study, especially at the Ph.D. level.

Aimee was tenacious, however, in her early days pursuing the study of birds, taking on several internships along the way before the Ph.D. opportunity came to fruition.

Briefly mentioning a couple of them here, one of Aimee’s internship experiences included spending a summer on the very remote tundra of the Kodiak National Wildlife Refuge, on Kodiak Island, Alaska, searching for seabird nests of the remote nesting Kittlitz’s murrelet, a small, grey-brown seabird that nests alone on the tops of rocky mountains.

Another internship opportunity a year later took Aimee to Awashima, Japan where she spent 6 weeks on a small island helping a research crew search for streaked shearwater nests (a seabird similar to an albatross) and capturing them at night to attach GPS transmitters to these unique seabirds.

She had several others internships along the way, but suffice it to say, Aimee was willing and ready to do whatever it takes to study birds, no matter how remote the location was or how harsh the conditions were she had to live and work in.

And all of her internships and hard work at Cornell University paid off as she was offered a Ph.D. opportunity at Utah State University studying pelicans.

Now, remember me mentioning boot-pulling marsh mud and pelicans as a fun-filled afternoon for yours truly?

Well, we are getting closer to that so just keep readings, it all ties in together in just a moment.

As I have mentioned, Aimee is currently studying the American white pelican.

More precisely, she is looking to track pelican movements with solar-powered GPS transmitters attached to pelicans for several interesting fields of study.

This includes trying to understand where pelicans go on their breeding grounds here in Utah as well as on their wintering grounds in Mexico and what migration paths they take.

By tracking the pelicans’ migration routes, Aimee can help identify the habitats pelicans prefer and use along the way which could possibly help protect these areas and, in turn, help protect the American white pelican.

Another field of study that has a very real application here in Utah is using the GPS data to better understand how pelicans use the local airspace, namely when, where, and how high they fly, in hopes of better understanding how to prevent bird-plane collisions at the Salt Lake International Airport.

Birds crossing paths with airplanes is a serious and frequent issue here in Utah, with thousands of acres of wetlands in very close proximity to the Salt Lake International Airport.

In fact, this problem has been in the news lately as just this year a plane carrying members of the Utah Jazz basketball team and the staff was struck by birds, forcing it to make an emergency landing due to a fire in at least one of the engines.

It was later reported that at least 4 birds larger than the average gull, a common bird around the airport, hit the plane shortly after takeoff, giving it the distinct possibility of being pelicans that struck the aircraft since they frequent the area due to the nearby marshes.

Aimee is also working on trying to determine if weather radar can detect flocks of pelicans by using GPS points to know if a pelican is present in a radar image pixel.

If pelicans can indeed be seen by weather radar, it would allow pelicans to be tracked and their movements monitored without having to solely rely on capturing and attaching GPS transmitters to the birds, something that isn’t an easy thing to do by any means.

So, as a result of all of this, GPS transmitters need to be attached to pelicans, as many birds as possible, in fact, to help gather much-needed data regarding local pelican movements and annual migration routes for all of Aimee’s fields of study.

This is how I met Aimee on the Bear River Migratory Bird Refuge auto tour route, in her efforts to catch and tag pelicans with GPS transmitters for her Ph.D. research.

It’s not an easy job to catch a pelican, especially in a wetland with such conditions where the knee-high soft mud literally pulls your boots off when you walk.

How do I know this, you might ask?

Well, being the determined nature blogger that I am, trying to bring you real-world stories about birds and the natural world around us no matter what it takes, I decided to volunteer and help Aimee catch and tag pelicans.

Honestly, I really wasn’t prepared or fully understood what it takes to catch a pelican in a wetland, but now I do and it’s not an easy thing to do because of the wet and mucky environment pelicans live in.

The following week after initially meeting Aimee, I spent a couple of days at Farmington Bay WMA in an effort to catch and tag pelicans with her, a couple of other volunteers, and her parents that came to town to also help with this project.

Simply put, in order to catch pelicans, modified leg traps are placed under shallow water in loafing areas pelicans frequent after fishing.

The leg traps, altered as to not injure the pelican but strong enough to hold it until Aimee can get to it for removal, are staked out in the shallow waters where a pelican would step in one and be detained for a few minutes until it was removed and the pelican tagged and then released back into the wild.

This means wading or canoeing out to a common loafing spot used by pelicans, which is sometimes surrounded by deep, boot-grabbing mud.

After the traps are set, the watching starts from a distance through a spotting scope.

If and when a pelican is caught, Aimee and her volunteers, myself included, were prepared to speedily head out to the bird and quickly tag and release it.

During my 2-day stint with Aimee, we only caught and tagged one pelican, but that in itself was a thrill for this birder as, after her tasks were completed, I was awarded the opportunity to hold and release the pelican, affectionately named Calvin for the study, back into the wild.

Overall, Aimee caught, tagged, and released 4 American white pelicans this summer and she plans on trying to add to that total for her research studies next summer as well.

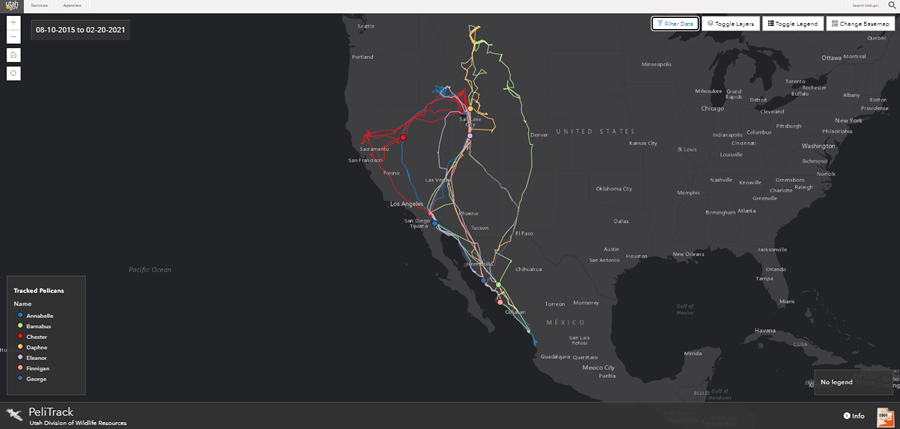

The interesting thing is, this tagging pelicans with satellite transmitters activity has been going on for several years now in Utah, and their migrations and movements can be viewed online by you and me through the Pelitrak website set up by the Utah Division of Wildlife Resources.

Overall, since the pelican tagging program started in 2014, 72 pelicans have been tagged with solar-powered GPS transmitters and their data recorded on the Pelitrak website.

And now Aimee is adding her efforts and research to the Pelitrak project to help monitor the migration and movements of pelicans through GPS transmitters.

Maybe for most people, spending several days in a swamp, drudging through knee-high mud, doesn’t sound like an exciting adventure of any kind, but for me, it was one of the most incredible experiences I have ever had.

And now when I see Calvin the pelican’s migration route on Pelitrak, I can honestly say I know that large white bird as I held him in my hands for a few moments before putting him back on the wing so he can help us learn more about pelican migration.

Good luck to Aimee on her Ph.D. studies at Utah State University, it was a pleasure to help in your research efforts.

And good luck as well to Calvin the pelican, I hope we get to see you again someday on Pelitrak, as well as at Farmington Bay WMA.

If you are into birds like I am, I offer you to head on over to my subscribe page and sign up for email notifications for future blog posts.

I can’t guarantee any more pelican adventures quite like this one, but every day I get to be out in nature watching birds for this blog is an adventure to me.

We appreciate your readership and support for this website and ask for your help in getting the word out by sharing this or any other blog post you find interesting on your favorite social media outlet.