Now this may sound strange to some of you but for a long time now, anytime I see an American white pelican in fact, I get this constant craving to someday make the long journey to the very remote and desolate Gunnison Island, a pelican rookery that’s quietly stashed away in the northwest corner of the Great Salt Lake.

See, I told you it sounded strange, didn’t I?

But that’s just how I roll when it comes to photographing and writing about birds and nature.

I will literally go just about anywhere and do just about anything, all legally of course, for this website in an effort to show just how amazing our natural world really is in hopes of getting others interested in both enjoying and helping protect our natural wonders.

To give it some kind of comparison and to put my passion for pelicans into some kind of context, however, Gunnison Island is, well, my “Galapagos Island” of sorts, a dry, desolate, and highly protected pelican paradise that maybe only a borderline crazed birdwatcher like myself could love.

Gunnison Island, owned, managed, and protected by the Utah Division of Wildlife Resources, is a very important colony breeding ground, known as a rookery, for American white pelicans where thousands of these graceful birds come to nest and raise their young each summer.

This remote island is located in the far northwest section of the Great Salt Lake and is strictly off-limits to the public, including a one-mile halo around the island for plane, boat, and all other forms of human traffic, to protect the large pelican breeding colony which are known to be very susceptible to abandoning their nests from disturbances of any kind.

In a recent correspondence with John Luft, Great Salt Lake Ecosystem Program Manager with the Utah Division of Wildlife Resources, it was made known to me that upwards of 21,000 breeding pelicans have been seen at Gunnison Island in past years, making it one of the largest American white pelican rookeries in North America.

Luft also mentioned wildlife officials have counted over 80,000 pelicans in previous years during their waterbird census flights over the Great Salt Lake and adjoining habitat areas during spring and fall migration timeframes.

Needless to say, with thousands upon thousands of these graceful birds migrating both to and through Utah, the Great Salt Lake ecosystem, as a whole, is a vital piece of habitat for the American white pelican, and Gunnison Island, in particular, is an extremely important breeding ground for the overall pelican population as well.

There have been other smaller pelican rookeries in Utah in years past but all have been abandoned, quite possibly due to disturbances, and why the remoteness and the lack of access to Gunnison Island is ideal and very important for breeding pelicans here in Utah.

But, unfortunately, there is a problem with Gunnison Island and the breeding pelicans that stems from how we here in Utah, and to a smaller degree Idaho and Wyoming, use water from our rivers as well as how the prevailing climate has been, well, a bit parched the past few years, to put it mildly.

Each year during the month of July, John Luft, biologists, and personnel with the Utah Division of Wildlife Resources make the long journey to Gunnison Island to capture, count, tag, and release that year’s pelican offspring while they are still flightless in an effort to help track and learn more about pelicans and pelican migration routes.

This summer, however, the year when it looked like I was finally getting the opportunity to travel with Luft and DWR personnel to the island to photograph and write about this incredible place and most interesting of bird banding projects, the event was canceled due to, well, lack of pelicans on the island.

In my correspondence with Luft, I learned several aerial spring nesting counts over the island resulted in about 3000 pelican nests in May, less than 1000 in June, and about 50 young pelicans remaining in July with many of the other nest sites left completely abandoned.

A quick island check during a later aerial count in July for a different bird species in the area resulted in there being no pelicans still residing on Gunnison Island and, consequently, the upcoming pelican banding project was abruptly called off.

So what happened exactly to cause such a demise on this remote island rookery that once had as many as 21,000 nesting pelicans in years past but was now reduced to a mere 50 chicks this summer, young pelicans that, sadly, may or may not have survived the elements in their own right?

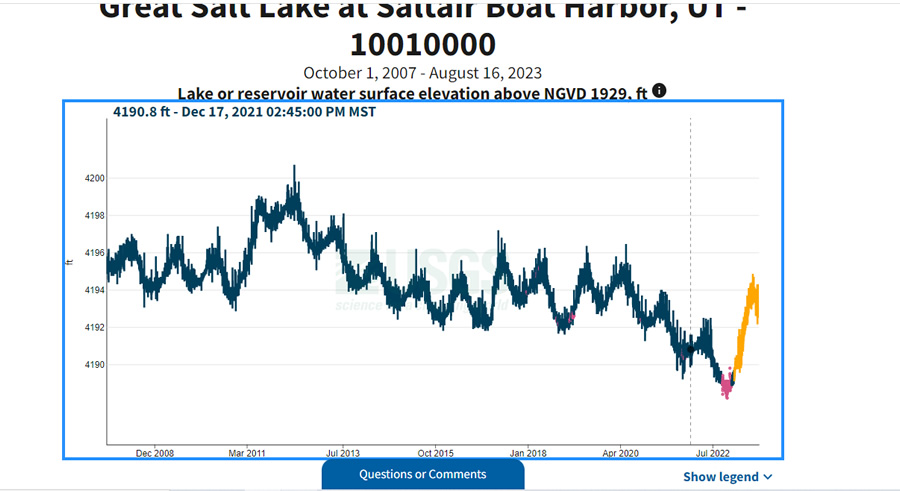

Well, to answer that question we need to back up a few years, around 2016 to be exact, and talk about the shrinking Great Salt Lake from both the ongoing drought and a thirsty society that pulls a large portion of water from northern Utah’s rivers before it even hits the lake.

Since 2016, both of these factors have caused Gunnison Island to no longer be labeled an “island”, per se, as the receding lake has left it pretty much high and dry and nothing more than a large, arid mound of dirt protruding out of the surrounding dry lake bed.

And because Gunnison Island now being connected to the mainland with a sort of land bridge, one, unfortunately, that both humans and coyotes can easily traverse, it is believed the resulting disturbances have caused the pelicans to greatly abandon their nesting efforts, resulting in extremely poor nesting success’s the past few years.

In fact, yesterday’s conversation with Ashley Kijowski, manager of the Eccles Wildlife Education Center at Farmington Bay, revealed that a coyote den was discovered on a recent trip to the island.

That discovery most certainly puts an exclamation point on how coyotes have taken advantage of the lack of formidable water around Gunnison Island and most likely are having a large influence on pelicans abandoning their nests due to their ease of access now with the island.

I know what you are thinking because, interestingly enough, I was thinking it too until I started to do some research for this blog post.

This past winter and spring, Utah received a record amount of snowfall and moisture, causing the Great Salt Lake to rise this year nearly 5.5 feet above its record low level of around 4188.7 feet above sea level recorded November 5, 2022 before it started to fall again late this summer.

So the question remains why is Gunnison Island still not an island now with so much water hitting the Great Salt Lake in one year?

Excellent question my friends and one I was struggling with when I saw a recent aerial photograph of Gunnison Island showing it is still not an island, not even close by the way, which surprised me to no end.

In 1959, the Great Salt Lake was changed forever when an earthen causeway, similar to the Antelope Island causeway, replaced the old wooden train trestle bridge laid in 1902 by the Southern Pacific railway.

Simply put this new route that was created back in the day provided a shortcut across the lake that still to this day saves the current owner the Union Pacific railway time, money, and fuel.

In short, the 20-mile-long Great Salt Lake Causeway split the lake into two parts, the north arm where Gunnison Island resides and the rest of the lake on the south side of the railway that hits shore once again on the southernmost tip of the Promontory Mountain range.

Originally 2 large concrete culverts were placed under the railway so the salt water and even small boats could move back and forth between the two sections of the lake but after a few years, the causeway sunk about 15 feet, causing the culverts to crack and both were closed and filled in to avoid damage to the railway.

So for many years, the only real water flowing into the north arm was from water seeping through the rock and earthen causeway, forcing the salinity of the north arm to go up dramatically over time.

(With this aerial view of the Great Salt Lake and the differences in water color, it’s easy to see Gunnison Island in the north arm, the Great Salt Lake Causeway that splits the lake, and the Bear River Migratory Bird Refuge, a common feeding ground for both nesting and non-breeding American white pelicans in northern Utah. Water flowing from the Bear River through the refuge and out to the lake is shown by the dark line.)

But in 2016, construction on a new 180-foot railway bridge was finished on the causeway, and the earth underneath the bridge was removed to allow water to freely flow once more between the two sections of the Great Salt Lake.

Since that moment when the Great Salt Lake Causeway was breached and water began to flow freely once more, the saltier water of the north arm started to mix and raise the salinity of the south arm.

And with the Great Salt Lake continually receding year after year from both drought and overconsumption of water from all the rivers that feed and sustain the lake, including the Bear River which helps support business, communities, and agriculture in Utah, Idaho, and Wyoming, the salinity of the south arm of the lake continued to rise to potentially unhealthy and harmful levels for brine flies.

I’ll fast forward this story a bit to February 3, 2023, when Governor Cox issued an executive order directed the Division of State Forestry, Fire, and Lands to raise the Great Salt Causeway berm, a small earthen dam of sorts under the 180-foot train bridge that can be raised or lowered depending on water flow needs of the lake.

By raising the berm nearly 5 feet this spring, water is now being restricted from flowing into the north arm of the Great Salt Lake.

And by thusly keeping all the incoming river water from Utah’s record-setting winter in the southern portion of the lake it is hoped the high salinity levels that are causing great concern for the brine fly breeding efforts can be reduced to more appropriate levels before, well, some kind of ecological disaster occurs that will not only adversely affect the brine shrimping industry but the millions of migratory birds that feed on the brine flies and shrimp each fall just before they migrate south for winter as well.

In fact, while on my impromptu visit to the Eccles Wildlife Education Center at Farmington Bay yesterday, I was informed that birds such as the Wilson’s phalarope, as just one example, feed heavily on the brine flies before they make their non-stop flight to Argentina.

Eared grebes are also known to double their weight before migrating because of the brine fly and shrimp ecology living in the Great Salt Lake.

(Wilson’s phalaropes feed heavily on brine shrimp before their long fall migration to Argentina. For short nature clips like this one and interesting stories about the natural world around us, check out our Bear River Blogger channel on YouTube for videos and updates from our travels while out in nature, both on and off of the famed Bear River Migratory Bird Refuge.)

So, all in all, this record-setting winter is a bitter-sweet pill to swallow with regard to the Great Salt Lake and all of the migratory birds and other entities that depend upon it.

It’s sweet to hear there has been some progress in raising the level of the Great Salt Lake this year, thus helping to try and lower the salinity levels somewhat to protect the vital brine flies and the birds that depend upon them.

But, for me at least, it’s also a little sad to hear the American white pelicans still are struggling to breed because of very low water levels in the north arm of the lake despite so much water being available but kept in the southern end of the lake this spring, giving predators free-range on the once out-of-reach Gunnison Island that has been a thriving rookery in the past for thousands of pelicans.

It’s really not a total win-win solution for the lake yet but rather a much needed bandage to fix a rapidly growing and much larger problem with the lake’s salinity levels.

As a whole and no matter how you slice it, until there is enough water for both sides of the Great Salt Lake Causeway to each sustain life in their own unique ways this effort is a good first step in the right direction but only a good first step, one that hopefully can be built upon with help from both strong winters and more conservation efforts from all of us in the years to come.

I do worry, however, that if this trend of Gunnison Island not being an island anymore continues with no end in sight and predation and other disturbances on the island keep pelicans from successfully breeding on the island as a result, someday the pelicans might fully abandon the Gunnison Island altogether and Utah would lose out on one of the largest breeding colonies of pelicans in North America.

The only consolation I have from that fear is John Luft affirmed to me that American white pelicans can live up to 20 years or more and these older birds will hopefully keep coming back to try again and again, year after year, because they have done it for so many years prior and to them this is their preferred nesting location.

But even so, Luft did mention he and the Utah DWR are greatly concerned that if this continues and pelicans are unsuccessful in rearing a chick year after year, someday they might abandon it altogether, possibly never to return.

This was the first year there was a total nest abandonment on Gunnison Island for pelicans, according to Luft, which does increase my concern that total island abandonment might be closer than it is further away.

There is so much beauty connected to the Great Salt Lake, from its grand sunsets to its millions of migrating birds and thousands of acres of wetlands, to its recreation and industry elements, to the effects it has on our weather, to, well, just the plain and simple serenity and openness of it all.

Spend some time learning about and visiting the Great Salt Lake and it won’t be long before you will find all of this is worth protecting by finding solutions to keep more water in the lake, both in the south and north arms so American white pelicans can once again breed and thrive as well as American avocets.

I’ll admit, saving the Great Salt Lake in its entirety, both the south and north portions, will be no small feat by any means with so many competing demands for water these days.

But with help from the weather each year and a lot of help from how we all use water from the rivers that feed the lake, maybe, just maybe Gunnison Island can once again be an island again and the American white pelican can stay put and keep filling the skies of Utah with their graceful wingbeats for years to come.

If you’re like me, an avid birdwatcher and lover of nature as a whole, I offer you to head on over to our subscribe page and sign up for email notifications for future blog posts like this one.

It is our effort and intent to not only entertain but to inform and educate all who stop by our website for a spell about the incredible sights and sounds nature has to offer, both on and off of the famed Bear River Migratory Bird Refuge.